Christopher Peacock, founder of his eponymous Norwalk, Connecticut–based cabinetry brand, had the good fortune to sell his company to British furniture maker Smallbone at the top of the market in September 2008—and the ill fortune to get caught up in the new owner’s subsequent bankruptcy just months later. Here’s how he brought his company back from the brink (and then some).

After Smallbone closed, I began negotiating with the banks to reacquire the business, which I felt was rightfully mine. The banks had little interest in helping me, so it took several months before I got any traction. I was committed to reopening the company I had spent 16 years building, but in truth I had no idea if I could. I felt so frustrated that we had achieved so much but couldn’t finish the job. That’s what drove me to restart.

I finally purchased the business assets and set up a new company in June 2009. I used my own money and chose to avoid investment. I signed new lease agreements; reopened showrooms in Chicago, San Francisco, and Greenwich, Connecticut; and rehired about 60 staff—half as many as before. I started making cabinetry for the clients who had been affected by the shutdown, absorbing their lost deposits in order to buy back some goodwill, without which I believed I could never rescue my brand and my reputation.

Since I self-funded the new company, I had to be lean, rethink everything and rebuild one step at a time. At first there was little to no business, and everyone [on the team] was expected to do more and work harder. In some cases, I had to agree [to] special payment terms that gave clients a level of comfort. Our competitors used an inaccurate version of the facts to dissuade clients from hiring us, so I had to work twice as hard just to combat that. I found that honesty and personal contact worked: [Because I showed] my passion for the company and brand, clients trusted me and my team to deliver on our promise.

We opened up with a different attitude from the outset, and the results were pretty immediate. I started to invest in new products, stronger management, better machinery and improved technology. This allowed me to provide clients with more options and a greater level of customization. I opened up the showroom in New York’s D&D Building in 2010, during a period when no one was signing leases, and that timing paid off. The economy was starting to gain traction and people were finally spending money again.

It wasn’t until 2010 that I really saw things come together, and we’ve grown tremendously since then, adding several showroom locations, including Nashville and a new street-level space in Boston this spring. We are now up to more than 90 employees, with a larger footprint and more locations—almost double the size of the company that sold to Smallbone—and we continue to grow healthy margins.

____________

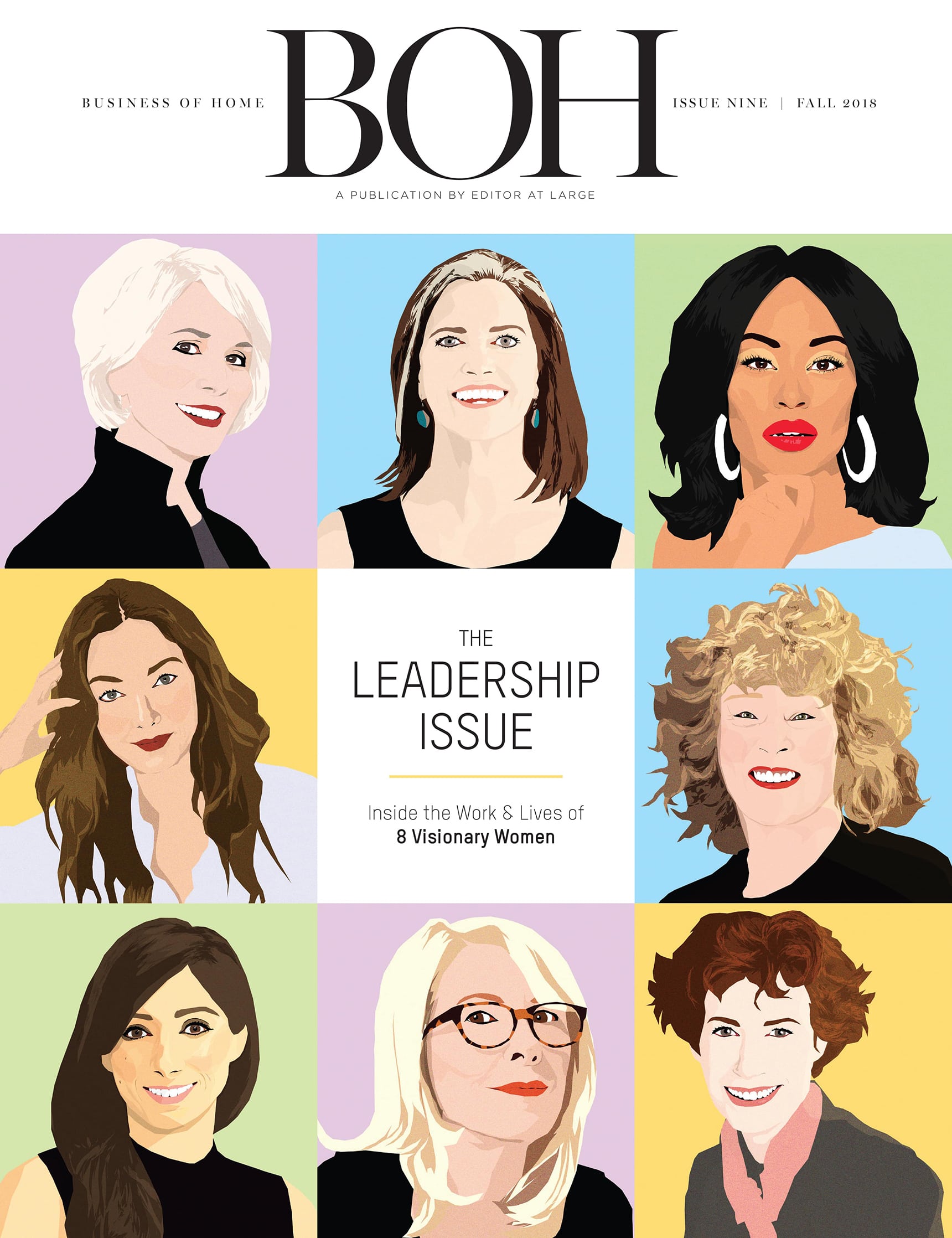

This article is part of a series profiling seven industry leaders who chose boldly when their businesses hit a fork in the road. Find out how each sidestepped fear at one make-or-break moment in order to blaze a trail to success.

Fundraising Freethinker: Kathy Kuo

Fundraising Freethinker: Kathy Kuo

How rethinking fundraising helped this designer grow her business

Showroom Maven: Katrena Griggs

Showroom Maven: Katrena Griggs

How one Atlanta showroom veteran launched her own brand

Space Innovator: Analisse Taft-Gersten

Space Innovator: Analisse Taft-Gersten

How a coffee bar transformed ALT for Living’s showroom model

Marketing Rebel: Lee Mayer

Marketing Rebel: Lee Mayer

How an unconventional marketing decision kept Havenly in the game

Radical Curator: Ben Moir

Radical Curator: Ben Moir

How one brand cut nearly half of its offerings—then saw revenue spike

Trade Renegade: Catherine Connolly

Trade Renegade: Catherine Connolly

How transitioning to trade-only saved Merida

Homepage photo: Christopher Peacock's Lambourne Collection | Genevieve Garruppo